The Empiricization of Computer Science

Scientific disciplines, like nations, have their own founding myths. These may sound inconsequential at first, but they deeply shape how disciplines see themselves, what they value, and what they believe their role in the world ought to be. I’d argue that computer science was built upon founding myths around theory and system building. Princeton has a very exciting course called “Great Moments of Computing,” where Margaret Martonosi walks students from the foundations of digital logic and differential privacy to the creation of network protocols and the computer mouse. In a sense, these are the closest equivalents computer scientists have to a Durkheim, a Smith, or a Freud.

Yet the nature of computer science has changed tremendously: it is now an empirical science, driven by observation and experiment as much as by theory and construction. If you don’t believe me, spend 5 minutes going over the best paper awards for three conferences in different subfields in CS. If you did so in 2025, you might have found papers like “Characterizing and Detecting Propaganda-Spreading Accounts on Telegram” (USENIX; Security and Privacy), or “Examining Mental Health Conversations with Large Language Models through Reddit Analysis” (CSCW; Human Computer Interaction), or “Scaling Depth Can Enable New Goal-Reaching Capabilities” (NeuRIPS; Machine Learning). The first two papers describe online user traces, to understand sociotechnical phenomena (Online Propaganda, people using LLMs to talk about mental health issues), while the latter is a full-blown examination of what happens when you do self-supervised RL with very deep neural networks.

This empiricization of Computer Science seems to have happened independently across subdisciplines, and I argue that the reasons are two-fold.

Reason #1: Socio-technical integration of computing

First, computer scientists steadily broadened the scope of what they treated as “a computing problem.” Part of this is simply baked into the field’s origins: computing inherited deep roots in mathematics and engineering, but it also grew up in constant contact with other disciplines: think cybernetics or cognitive science As computing technologies matured, they also began to fade into the background of everyday life, becoming infrastructure rather than an object of conscious attention. In his seminal “The Computer for the 21st Century” essay Mark Weiser captured the consequence of that transition: “only when things disappear in this way are we freed to use them without thinking and so to focus beyond them on new goals.”

Privacy is a particularly vivid example. In an earlier framing, “privacy” looks like a technical property of systems—confidentiality, secure channels, access control—problems that naturally invite cryptographic solutions. But as privacy disputes increasingly played out in real social settings, the field had to confront privacy as something defined by people’s expectations, norms, and context. Nissenbaum’s theory of contextual integrity crystallizes this shift by tying privacy to whether information flows are appropriate relative to contextual norms. Even when the cryptography is excellent, privacy can still fail at the human interface: if users pick weak or reused passwords, attackers don’t need to “break” encryption, just to log in!

Another example is the evolution—and very existence—of the field of human–computer interaction. SIGCHI’s early curricular definition makes the scope expansion explicit: HCI is concerned with the design, evaluation, and implementation of interactive systems “for human use,” and with “the study of major phenomena surrounding them.” In other words, once the object of study is interaction rather than computation alone, empiricism is no longer optional: you need user studies, experiments, field observations, and iterative evaluation to know whether a system is usable, safe, or meaningful. Over time, HCI also widened what it counts as “interaction”. Bødker (2006) describes the field as moving from a first wave rooted in human factors and design, to a second wave shaped by cognitive science, and then to a third wave emphasizing situated meaning, values, and social context.

Just as HCI institutionalized user studies, the systems and networking communities institutionalized measurement itself. SIGMETRICS emerged as a way to measure the differences in performance across computers (a subtly challenging task). And while you could argue there’s no “societal factor” here, this changed the moment the Internet became a live, evolving, operational system. Core properties of the Web “worked” were elusive because they relied on how people and institutions used it in practice. This led to the need for a new, much more empirical type of research that required sophisticated measurement infrastructure. For instance the SIGCOMM Internet Measurement Workshop (2001) explicitly asked for work that improves understanding of how to collect/analyze measurements or “give insight into how the Internet behaves,” and it stated bluntly that papers not relying on measurement were “out of scope.”

Finally, the rise of computational social science blurs the boundary between “CS papers” and “social science papers.” Lazer and colleagues open their manifesto with the observation that “we live life in the network,” leaving digital traces that can be assembled into detailed pictures of individual and collective behavior. In that world, it becomes increasingly hard to draw a clean line between disciplines: the same project may involve building data pipelines, designing machine learning models, running quasi-experiments and interpreting results through social science theories. Go to a venue like IC2S2, and you’ll find people in CS working on exactly the same kinds of problems as people in Sociology or Political Science.

Taken together, these shifts mark a quiet redefinition of the discipline: as computing “disappeared” into infrastructure, the unit of analysis stopped being the machine in isolation and became the human–system–institution loop.

Reason #2: The Triumph of Empiricism

Second, you have the triumph of empiricism, particularly in machine learning. If you dial back to the late 90s and early 00s, neural network, or “connectionism,” was remarkably unfashionable. In a 2015 interview with IEEE Spectrum, Turing Awardee Yann LeCun said: “I have very little patience for people who do theory about a particular thing simply because it’s easy—particularly if they dismiss other methods that actually work empirically, just because the theory is too difficult. There is a bit of that in the machine learning community. In fact, to some extent, the “Neural Net Winter” during the late 1990s and early 2000s was a consequence of that philosophy; that you had to have ironclad theory, and the empirical results didn’t count.”

But at the same time as neural networks were “shunned,” something else was happening in Machine Learning Land: the discipline started to become increasingly oriented around shared tasks and competitions. Perhaps this was only natural for, as one of our founding myths is the Turing test: a challenge were a machine must exhibit behavior indistinguishable to that of a human. Isabelle Guyon, a co-inventor of the support vector machine, shares a brief history of data in her 2022 NeurIPS talk titled “How ML is Becoming an Experimental Science”. She notes that the field evolved from toy data, to shared datasets (most prominently made available in the UCI ML Repository) to larger datasets that were often embedded in a explicitly competitive context. Some prominent early competitions include the KDD Cup, hosted by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), and competitions hosted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), one of which introduced the now famous MNIST digits database.

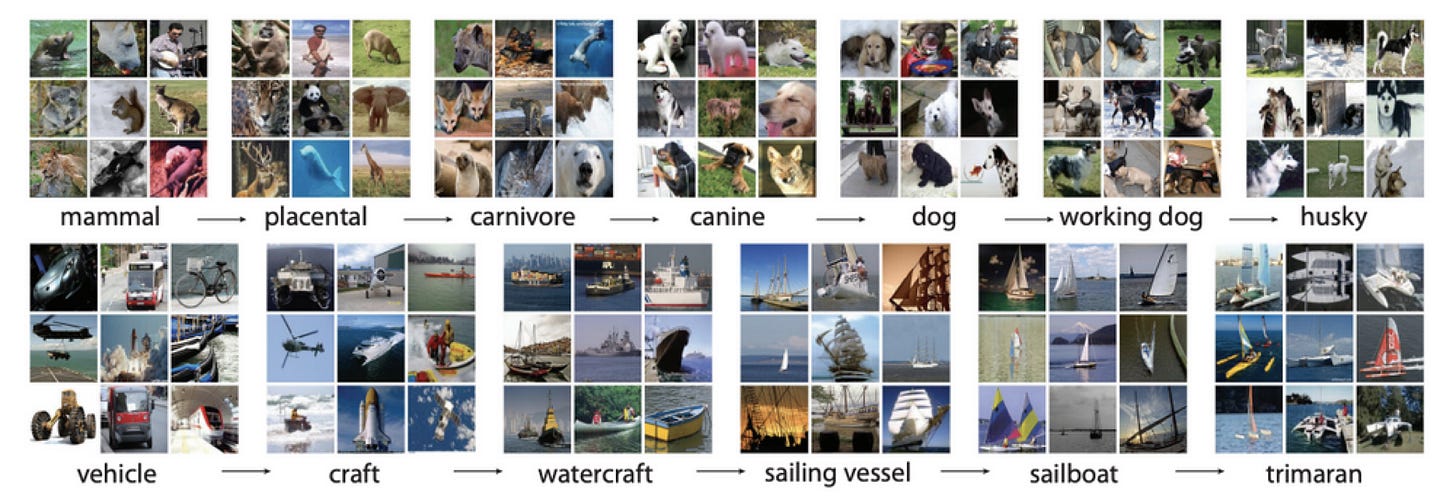

As compute and data became plentiful, deep learning flourished. A canonical turning point is AlexNet’s win at the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). ImageNet was unusually ambitious for its time—an effort to scale visual recognition with millions of labeled images. And ILSVRC distilled that vision into a standardized benchmark of 1,000 categories with about 1.2M training images. In 2012, Krizhevsky, Sutskever, and Hinton trained a large convolutional network on this dataset and crushed the field: their entry achieved a 15.3% top-5 error, compared to 26.2% for the runner-up.

The increasing adoption of doing “what works” marked an inversion of how knowledge ought to be accumulated in machine learning. Before, experiments were seen as confirmatory. The idea was that better theory would lead to better models, and that experiments were a way to confirm that a model was indeed better (and that perhaps the theory did not have any flaws). For example, in a 1999 piece, Vapnik describes the rise of support vector machines in the mid-1990s as learning algorithms “based on the developed theory,” explicitly positioning statistical learning theory not only as analysis but as a driver of practical algorithm design.

In the deep learning era, the direction often runs the other way: models are frequently guided by intuition and engineering heuristics first, with theoretical framing arriving later (if at all). The original dropout paper is almost playful about this, stating that the motivation for the method “comes from a theory of the role of sex in evolution (...). A closely related motivation for dropout comes from thinking about successful conspiracies” (Srivastava, 2014).

Theory, then, often enters as post hoc explanation and consolidation. A prominent follow-up to dropout was literally titled “Understanding Dropout,”, and it set out to formalize what dropout is doing (as averaging/regularization, and in simple settings as optimizing a regularized objective), giving a theoretical account for an empirically successful trick. A similar arc shows up in the “double descent” story: modern overparameterized models displayed test-error behavior that looked inconsistent with the textbook bias–variance tradeoff, and only afterward did theory work emerge to reconcile the classical U-shape with the empirical “interpolation peak” and the subsequent performance improvement at larger scales. Again, theory did not inform that models should be overparameterized so that at some point, the error rate would go down again. People just tried doing things and some of them worked well.

And someone might argue: “But this is only machine learning—CS is so broad!” But is it really? The meteoric rise of machine learning—and, more recently, generative AI—has started to behave less like one subfield and more like a method layer that percolates through the rest of computer science (and increasingly, through the sciences more broadly). In 2024, the Physics Nobel prize went to Hopfield and Hinton “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks,” and the Chemistry prize went (in part) to Hassabis and Jumper for an AI model that solved the protein-structure prediction problem (AlphaFold). Mathematics may be at the cusp of a revolution in which language models become integral to cutting-edge proofs—as Terence Tao’s recent account of the human–AI collaboration suggests. On the CS side, conferences like MLSys exist precisely because “systems” and “machine learning” have become deeply entangled—enough to warrant a dedicated flagship venue at their intersection. And in HCI, a growing slice of the field is now about designing with the inherent messiness of language models, leading to new interface patterns and evaluations aimed at helping users cope with these failure modes.

So what?

This whole rant started as a “we don’t have empiricism as a founding myth.” But then, I’ve spent quite a bit of ink arguing that the empiricization of computer science has already happened. So what really is the problem here?

The problem is how we became empirical. Too often, we practice a kind of post-hoc, radical empiricism: run what we can run, keep what works, and only afterward scramble for the vocabulary of validity, uncertainty, and explanation. The tell is that we keep patching rigor in after the fact (through checklists, artifact badging, and community process fixes) because we never made principled empiricism a first-class part of the curriculum.

Watch for the next post for more on that and on what a more principled empiricism would entail in CS.

I am often bemoaning how HCI became a purely empirical field. Even in settings where statistical theory is clearly relevant to defining what we want humans to achieve (e.g., better decisions from use of model predictions or visualizations), there's a tendency to see theory as irrelevant. Meanwhile, many user studies, when you analyze them theoretically, are more or less dead in the water... what they hoped to find was unlikely from the get-go.

Interesting post! At some points it felt like you were arguing that CS is evolving into a "purely experimental/empirical" science, which I would push back against. I see it more as CS maturing into a place where theoretical/conceptual work is no longer the ultimate goal, but another piece of the puzzle that should take into account and communicate well with the empirical evidence and work. Of course, this might just be my survival instincts as a theoretician kicking in :).

This post certainly reminded me of Recht's post on "Computational Mythmaking", where CS being a discipline closer to mathematics was seen as a signal of value of the field. It does feel we are navigating towards a more balanced view of CS nowadays.